This is about building Auth HI!, a Chrome extension for injecting authentication headers. I built it over the 2025 Christmas break using a spec-driven workflow that mirrors how I learned to work in a chemistry lab.

This is part of an ongoing series on what it means to be a software engineer in the age of AI.

Over the 2025 Christmas break, production work paused, leaving room to approach a problem more deliberately.

Unlike the November 2025 code freeze before Thanksgiving, when I built dev-agent through open-ended exploration with AI, this time I wanted something contained — a real problem with real constraints, small enough to finish, but rigid enough to push back when decisions were unclear.

As an engineer, I tend to work best with some structure in front of me. In day-to-day work, that usually means tickets or notes — a way to keep thinking explicit so execution stays steady. There's room for exploration, but clarity usually comes from deciding first.

I studied chemistry in college and spent three years in the Hoye Organic Synthesis Lab. What drew me to organic chemistry was how sensitive the work was to conditions. A few degrees of temperature, a trace impurity — any of it could change the outcome entirely. Literature would say "slowly introduce HCl to the reaction mixture" without defining what slowly meant. You had to figure that out through trial.

That ambiguity made trial unavoidable. And trial in chemistry is expensive — time, materials, the risk of ruining intermediates you spent weeks preparing.

Organic chemistry teaches you to respect intermediates. You rarely see them in the final product, but they determine whether anything stable can be built at all.

Software has its own intermediates. State. Boundaries. Coordination layers. The parts that don't show up in demos, yet decide whether a system survives contact with reality.

That perspective shaped how I approached this project.

The blueprint

Every synthesis starts with the literature.

The blueprint was jstag — our data collection SDK that's been in production long enough to earn its confidence. It has to be dependable at the core while remaining open to extension, supporting a wide range of third-party integrations without collapsing under their weight.

I wanted to understand why it was shaped the way it was, and what kinds of failures it had already learned to absorb.

Around the same time, a colleague mentioned a spec-driven workflow during a pre–code freeze check-in, loosely inspired by GitHub's spec-kit. The idea was straightforward: slow the thinking down early and make dependencies visible before any code exists.

That combination stuck.

Before touching code, I opened specs/spec.md and wrote down what I wanted to exist:

- Clear responsibilities

- Predictable coordination

- Failure modes that surfaced instead of hiding

- Platform constraints treated as first-class

I didn't know how to implement any of it yet. The goal was clarity, not completeness.

Writing the spec forced decisions to surface early:

- What's the contract between components?

- Where do failures appear?

- How does the platform constrain behavior?

- What does "done" actually mean?

Writing a spec feels slow because it moves the hardest thinking to the front. That's usually where the leverage is.

The learning instrument

In the lab, you don't jump straight from reagents to a final molecule. You spend endless days babying the intermediates, so they are stable enough — or you make more stable intermediates if you have to — to enable an equally efficient path forward.

For this project, I built the learning instrument first: SDK Kit. I wanted to understand the architectural pressures in isolation before applying them to a real product.

SDK Kit wasn't a product goal. It was a way to make architectural pressures visible. Building it surfaced the same forces that shape jstag at scale, but in a form small enough to reason about directly.

Certain patterns emerged naturally:

- A plugin-based architecture that stayed composable and testable

- Clear boundaries around storage, pattern matching, and request interception

- Event-driven coordination, so components could evolve without tight coupling

Those patterns emerged through the work itself, shaped by the same constraints jstag has already solved in production.

Each piece followed the same rhythm. Before writing any code, I created a notes file — notes/issue-01-chrome-storage-plugin.md. I researched Chrome's APIs, documented trade-offs, made a decision, and wrote down why.

Only then did I implement.

That loop repeated across the core plugins:

- Storage (sync vs local vs session, quotas, failure modes)

- Pattern matching (URL rules, performance characteristics)

- Request interception (declarativeNetRequest, rule limits, visibility)

The commits reflect that cadence:

Dec 20 - feat: implement Chrome Storage Plugin

Dec 20 - feat: implement Pattern Matcher Plugin

Dec 20 - feat: implement Request Interceptor Plugin

The design lived in the notes. The code followed naturally.

By the time I turned to the Chrome extension, the core SDK Kit had settled at about 1,221 lines — compact, but dense with lessons about what actually holds up under pressure. Cursor tracked how I used the AI throughout the project. The patterns were revealing:

Learning in the loop

A large part of that learning came from how the work unfolded inside Cursor.

I spent most of the project pairing with Claude 4.5 Sonnet (thinking mode), using it to research APIs, draft specs, and break work down into plans. Those plans lived in a notes folder, serving as references I could return to when context faded or assumptions needed re-checking.

Cursor surfaced something I hadn't paid much attention to before: visibility into how I was using the tool, not just what I was building.

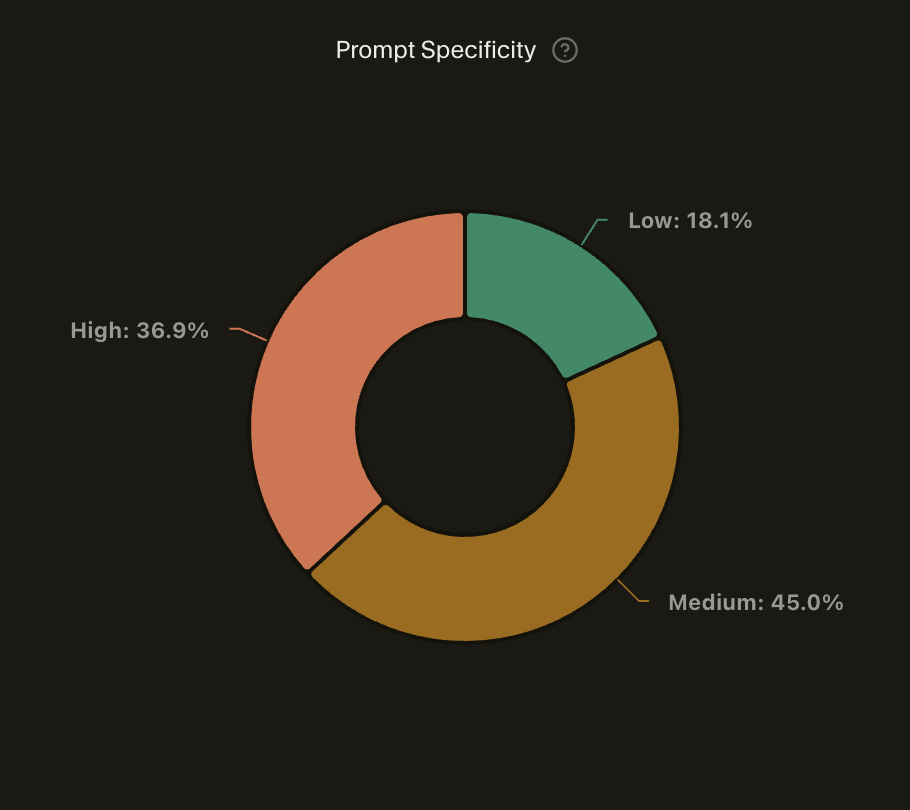

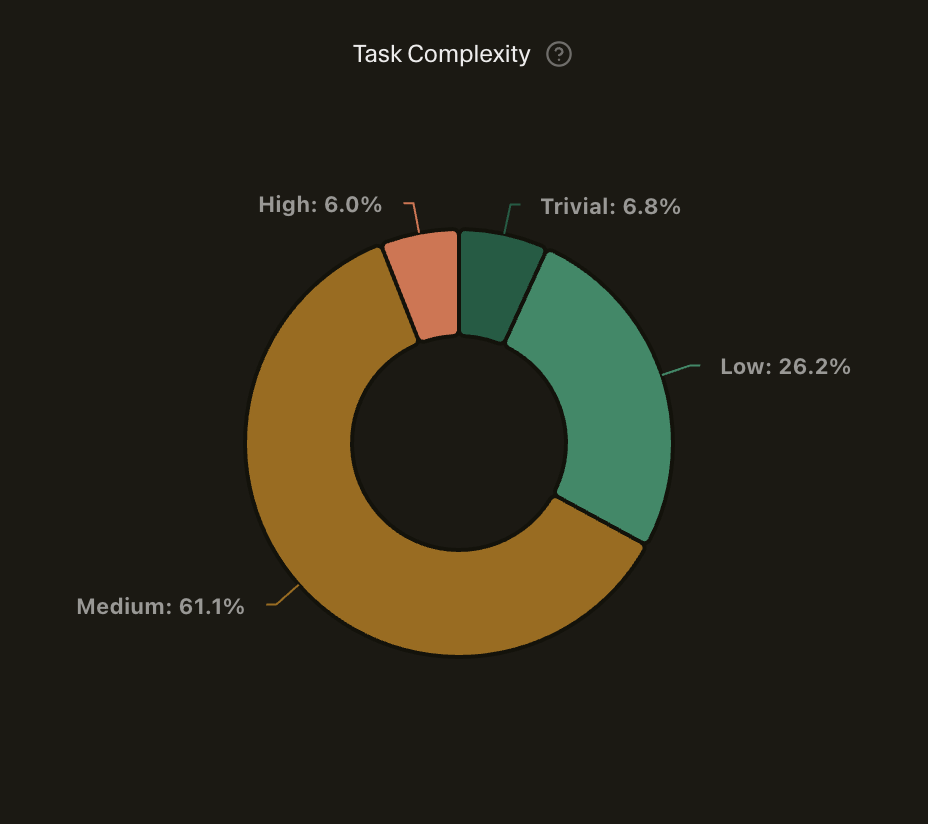

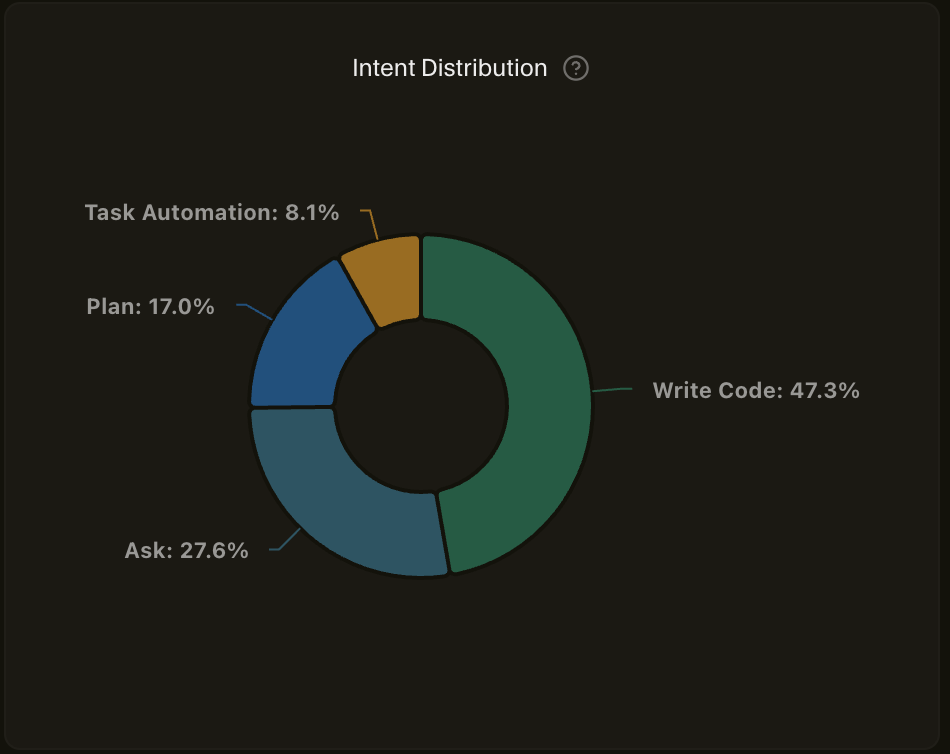

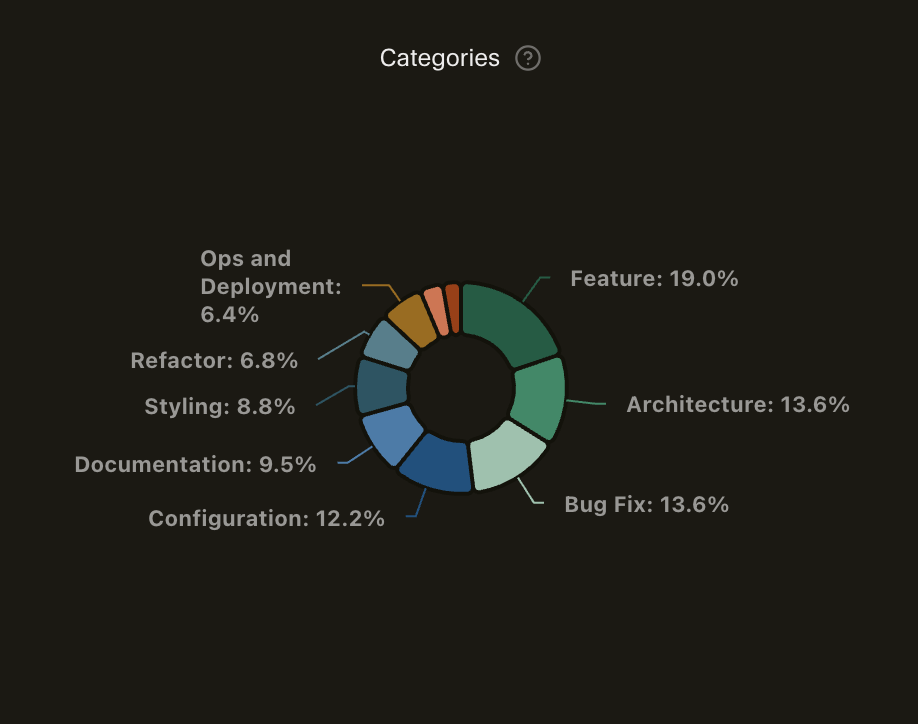

Most interactions clustered around medium prompt specificity and medium task complexity. The intent skewed heavily toward writing code and planning, with relatively little one-shot automation. Architecture, configuration, documentation, and refactoring all showed up in meaningful proportions.

That distribution mattered. The AI supported the work by externalizing reasoning, connecting dependencies, and maintaining momentum without replacing decision-making.

In that sense, Cursor became part of the learning instrument alongside SDK Kit — a way to observe my own workflow under constraint, not just accelerate it.

Most prompts landed in medium specificity — enough context to be useful, not so much that I was over-specifying implementation details.

Task complexity clustered around medium — the kind of work where the architecture was decided, but the implementation still required thought.

Intent skewed heavily toward writing code and planning. Very little one-shot task automation. The AI was a pairing partner, not a script executor.

The work spread across feature development, architecture, configuration, and documentation. No single category dominated — a sign of building something end-to-end rather than just coding.

The synthesis

With the intermediary in place, the final product became possible.

We used to rely on a lightweight Chrome extension for injecting authentication headers during development. It did one thing well: paste a token, define URL patterns, intercept requests, inject Authorization: {token}. Over time, it fell out of support.

Rebuilding that capability became an obvious synthesis target. The behavior was simple, the constraints were real, and the surface area was small enough to expose weaknesses quickly.

More importantly, it was the right place to apply the SDK Kit learning instrument. If the architecture was stable and easy to build on, the extension would make that visible immediately — and if it held up, the same event-driven, plugin-based foundation could support other SDKs or extensions without changing shape.

Over four days, I built Auth HI! on top of SDK Kit, verifying each step before moving on.

The git history became the lab notebook:

Dec 19 - chore: Initial project setup

Dec 20 - feat: implement core plugins

Dec 21 - feat: side panel with request tracking

Dec 22 - feat: enhance context bar with stats

Dec 23 - feat: add documentation site

Dec 23 - feat: rebrand to Auth HI!

Verification and production

Shipping to the Chrome Web Store served as verification.

Production surfaced gaps quickly:

- Service workers die mid-operation

- Users create dozens of rules

- Chrome's sync storage caps out at 100KB

- People switch machines more often than you expect

The plugin architecture kept those discoveries contained. Fixes stayed local. Nothing cascaded.

It felt familiar — like adjusting storage conditions after realizing an intermediate was degrading faster than expected.

Publishing the intermediary

I published SDK Kit to npm as @lytics/sdk-kit.

Publishing an SDK shifts the focus. Apps need to work. SDKs need to be understood. Contracts, event surfaces, examples, and migration paths all matter.

Documentation makes architecture visible.

What I'd change next

A few gaps became clear with real usage:

- Explicit plugin dependency declarations

- Stronger type guarantees across plugin boundaries

- Integration tests covering full lifecycle behavior

These are the kinds of issues that only show up once something real exists.

The lesson

This project followed a shape I recognize well.

There was existing knowledge to study. There were intermediates that needed care. And there were decisions that were far cheaper to make early than to revisit later.

jstag provided the blueprint. SDK Kit gave me a place to surface and understand the pressures involved. Auth HI! made those decisions concrete.

Most of the effort went into understanding and verification. The code carried that work forward.

What stood out wasn't speed. It was cost — the cost of trial, the cost of rework, the cost of discovering too late that something fundamental didn't hold.

AI shifted that balance in an interesting way. It made it easier to pause and ask whether I'd thought enough before giving in to the urge to build — the same tension I've written about before. The urge is still there. What's changed is how cheap it's become to interrogate it before committing.

Auth HI! is available in the Chrome Web Store. SDK Kit is open source on GitHub (soon).